Since Project-Based Learning centers around a specific problem or issue, it makes sense to start with clarifying and defining the problem. McCarthy (2015) proposes a “driving question” to kick off the PBL unit and that it must be focused on the content and understandings that students must know after completing the project. The culminating product becomes the solution or answer to the driving question and students are tasked with demonstrating the process for arriving at this solution.

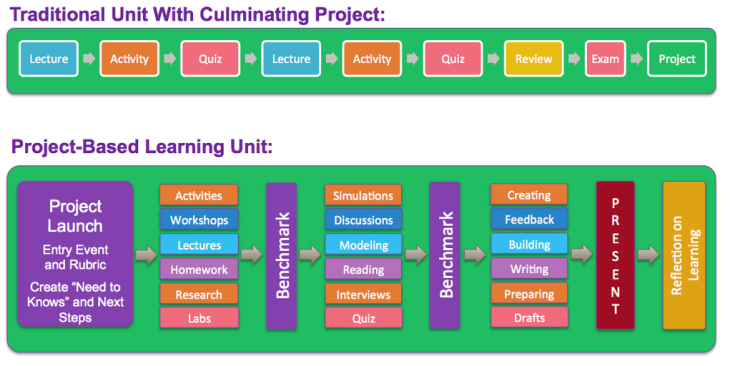

Consider this illustration (Curtis, 2013) of a traditional unit plan that ends with a project compared to a PBL unit that uses the process of a project to guide students in learning the context in a deeper and more meaningful context.

The last couple of years I have facilitated a youth development program for high school girls in San Francisco. The Envision program at Oasis for Girls is focused on supporting the young women to explore STEM (and other) careers, create a next steps plan for post-secondary education or train ing, and through technology training, build job readiness skills. The entire program is a PBL course and each group meets two hours/day, 2-3 days per week, for 12 weeks during the fall and spring or for 10 hours/week for eight (8) weeks during the summer. Our essential questions that drive the projects usually involve college, career, or job readiness topics and themes.

Pre-Planning Stage

I typically plan ahead for the program by preparing the Project Launch activities that will hook the students and guide us through a collective brainstorm about the topic. I have a timeline for the project that marks the main stages and benchmark checks along the way, but most importantly is the end date for project completion, so students know how much time is available. I also believe in creating a collaborative learning environment and modeling learning (especially from mistakes) for students. In the program, we practice job readiness skills by simulating a collaborative work environment as students work on their projects. The emphasis on collaboration “allows students to draw on each other’s perspectives and talents in order to more effectively devise solutions for the problem(s) at hand” (Ertmer & Simons, 43). I frame our collaboration as a working group with smaller teams tasked with specific projects that will contribute to the group’s goals and purpose. While each student has skills and aptitudes that they bring to the group and their teams, they are also tasked with building new skills and knowledge as part of their “work” in this group.

Stage 1: Project Launch

The collective brainstorm helps me to get an “entry point” understanding of each student’s readiness and get a sense of the group dynamic. Students review the rubric and scope of the project and determine individual learning goals and objectives. They also do a series of activities that help them whittle down our collective brainstorm information about the topic to arrive at a driving question and then form project teams based on common themes. Solomon (2003) points out that because the projects are focused on real topics and issues that the students (and their peers) are struggling with, they are motivated to do the work and contribute to finding a solution. By breaking up the issues into smaller problems, they can each focus on one question, but still learn from others who are working on their respective questions.

Stage 2: Team Roles, Initial Research & Project Proposal

Project teams meet to discuss their driving questions and determine research needs and methods. They also receive a rubric for team roles and responsibilities; every team member must have a distinct role and depending on the number of students, some students can have more than one role. Usually I expect each team to have a Manager, Presenter, Writer, and Organizer; every team member is a Researcher, and may assist with other roles, but they each have a role that is primarily their responsibility. Students may also add other roles as needed depending on their project. Activities during this stage include:

- Team research to refine their driving questions and project scope within the available timeline.

- Skill building workshops on research skills and methods, writing a project proposal, building consensus and conflict resolution, and using tech tools and programs relevant to the project.

- Teams discuss their project proposal with me, they submit a draft proposal, I review and return it with feedback, and they write their project proposal.

Stage 3: Benchmark check

Each team prepares and the Presenter introduces their project proposal to the entire group; their peers ask questions, give props and feedback, and share any relevant information or resources related to the proposed project. The project proposal is usually shared visually on a poster that stays up near each team’s work area. There is a progress poster next to it that shows the current team tasks and has a space for feedback from me and other groups. Oh the dreaded feedback session, where comments are critical or superficial and presenters can become defensive, right? Well, not if you build a culture of feedback and constructive criticism. “Formalizing a process for critique and revision during a project makes learning meaningful because it emphasizes that creating high-quality products and performances is an important purpose of the endeavor. Students need to learn that most people’s first attempts don’t result in high quality and that revision is a frequent feature of real-world work” (Larmer & Mergendoller, 3-4).

I often provide a short but clear rubric for giving feedback and encourage students to consider specific questions when giving feedback. The feedback should also be given in two parts, I see or think ____, because ____. Or I understand ____ but am not clear about _____. By also encouraging students to give “props” or (praises and compliments) about specific aspects of the project that impressed or appealed to them, the presenter is able to understand what is working and how to design the presentation to meet the audience’s needs and interests.

Stage 4: Research, Final Products, Guest Perspectives

Now the team gets to work on the research for their project; they discuss feedback and decide what recommendations to include and create a master list of tasks. They have identified guiding themes in their proposal and sources that would be important to include and reference. Jones (2006) lists four common elements of PBL that are relevant to each team’s process: student’s learning objectives are the problem that need to be solved through this project; the solutions should include an explanation as well as plan for implementation, students work in teams to tackle the problem, and anything that cannot be answered by their combined knowledge and skills becomes the focus of their research.

Research can be conducting experiments, survey, or interviews; finding information online – videos, articles, website, programs; and especially through homework – finding and collecting information in the community, interviewing friends and family, taking pictures or video, documenting events, stories, or other relevant information. Based on the topics, I (or the students) will usually invite content “experts” or guest speakers to meet with teams to share their perspectives and resources on the problem. One of the main activities is a group brainstorm about ideas for final products – we focus our discussion on the multiple intelligence and creating a master list of what products would meet each intelligence category. Teams use this list to decide what their final product will be and add relevant tasks to their timeline. Each team meets with me at least once during this stage for a progress check.

Stage 5: Benchmark check

Each team prepares and the Presenter introduces their final product idea to the entire group, they incorporate some initial information from their research to demonstrate why their product idea is appropriate and effective. Again, their peers ask questions, give props and feedback, and share any relevant information or resources related to the final product. This stage is usually done in a “science fair” format where only the presenter stays with the project poster and the rest of the team members visit each of the other team projects and give feedback. The presenter has 2-3 minutes to share their product idea with the “visiting” team and has a chance to answer questions; visiting teams write props and feedback on post-its and leave them with the presenter to review later with their team.

Stage 6: Bringing it all together

Teams finish up their research and decide what feedback to incorporate and make changes as needed. They begin developing and preparing for their presentation and have a meeting with me that includes a trial run of their presentation.

Stage 7: Presentations

Since presentations can take on a variety of formats, they are usually spaced out over a period of days. Larmer & Mergendoller (2010), also encourage us to invite a public audience, so that students’ work has real value and impact on others and they will be more invested in the quality of their work. We typically have others join our us for these presentations which can include other stakeholders – friends, family, community members, etc. Sometimes the final product is an event or it is launched “online” or even at a different location if the target audience is located elsewhere. Other teams and I complete a props and feedback form and each team writes an article style report about their presentation.

Stage 8: Reflection, Feedback/Recommendations, Celebration

With all the hard work that teams have put into their projects, it would not be complete without a celebration – snacks and drinks are mandatory and we don’t write anything but rather just focus on the discussions and interactions to reflect on the experience. We share our lessons learned, takeaways from the teamwork, and celebrate the impact their projects had on others.

Some of the driving questions that students have used include:

- What are my options after high school if I don’t’ go to college?

- What qualities and skills do employers look for and how can I get them?

- How will I get enough money to pay for college?

- How do I pick a school if I don’t know what I want to be?

- What makes a successful career woman?

- If I don’t like school, why should I go to college?

While the questions can be “googled” for quick answers, the projects focus on building a deeper understanding of the related issues and identifying steps that are unique to each individual. The projects then inform the specific steps in their plans that we develop together to meet their post-secondary education/training, career, and job readiness goals.

References:

Curtis, P. [Paul Curtis]. (October 15, 2013). PBL vs Doing Projects … a visual. #Edchat #PBL #PBLChat #NewTechNetwork. [Tweet]. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/paulscurtis/status/390188798618771456/photo/1

Ertmer, P. A., & Simons, K. D. (2006). Jumping the PBL implementation hurdle: Supporting the efforts of K–12 teachers. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-based Learning, 1(1), 5. Retrieved from: http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1005&context=ijpbl&sei-redir=1&referer=https%3A%2F%2Fscholar.google.com%2Fscholar%3Fstart%3D10%26q%3Dimplementing%2BPBL%26hl%3Den%26as_sdt%3D0%2C2#search=%22implementing%20PBL%22

Jones, R. W. (2006). Problem-based learning: description, advantages, disadvantages, scenarios and facilitation.Anaesthesia and intensive care,34(4), 485. Retrieved from: http://www.biomedsearch.com/article/Problem-based-learning-description-advantages/188739780.html

Larmer, J. & Mergendoller, J.R. (2010). Originally published as “7 Essentials for Project-Based Learning,” in Educational Leadership, 68(1). Reproduced and updated March 2012 by BIE.org with permission of ASCD. Retrieved from: http://bie.org/object/document/8_essentials_for_project_based_learning

McCarthy, J. (2015). Quality Instruction + Differentiation: Beyond the Checklist. Differentiated Instruction, Edutopia.org. Retrieved from:

http://www.edutopia.org/blog/differentiated-instruction-quality-beyond-checklist-john-mccarthy

Solomon, G. (2003). Project-based learning: A primer. TECHNOLOGY AND LEARNING-DAYTON-, 23(6), 20-20. Retrieved from: http://pennstate.swsd.wikispaces.net/file/view/pbl-primer-www_techlearning_com.pdf

I really like how you broke down integrating PBL into eight steps that are understandable and succinct. Reading through all the articles it is overwhelming at all the information that is out there, but your eight stage recipe made more sense than any of the articles to me. I wish I would have had this to read before I wrote my blog on Wednesday afternoon. I don’t have much, if any, experience with PBL, so I enjoy reading about it from my peers who know a lot about it and have used it successfully.

LikeLike

You did such a nice job breaking down the “recipe” for project-based learning. I am a visual learner so I really liked that you included visuals of the stages. I am going to refer back to your stages as I write my unit. The work you do with young girls sounds pretty awesome. I like that you included celebration at the end – I need to remember to include that.

LikeLike

I really like the idea of a “Project Launch” and I feel like it would really help students get into the project from the get go. I think it would also be a great opportunity to allow students to ask questions about the overall direction of the project. I also like having checks built into projects especially in younger grades. It is important to have check-in dates to help younger students learn how to pace projects. Nice post Mia!

LikeLike

You brought up several excellent points in your posting. One of the big hurdles for teachers who are unfamiliar with PBL will be adjusting to something new. Teachers who are used to a rigid, traditional setting may need the most coaching and encouraging. I have a feeling that kids will adapt faster than their teachers. Building in several “benchmark checks” will help kids stay on track and will help them understand the time requirements. This will be especially true for kids who are less organized or are procrastinators. Starting small and building up to larger, more complex PBL activities seems like a wise way to introduce this type of environment.

LikeLike

I think the check-ins at various points during the project are tremendously important. Since different groups or students will work at different speeds, it is nice to have those reminders that “you need to have X amount finished by Monday;” some students will then have to find the time to make sure they get up to speed by the check-in date. This is a problem I am currently dealing with in my unit. Some students finished quickly while others are still working, though part of that has to do with the options I gave them for presentation, which is another story…

LikeLike